I received digital files of Bob Dylan’s new album on Monday. Rough and Rowdy Ways is a masterpiece, a grand reinvention of his art for Dylan, and packed with sublime moments, great wit, savage violence, unbearable feeling. It’s something else. Now read on – this is the longer version of my review for The Arts Desk

When “Murder Most Foul” was dropped into an unsuspecting world under lockdown, the surprise among Dylan fans was palpable, given that eight years had passed since Tempest, filled by all those Sinatra covers and seasonal tours.

That it was a 16-minute epic that took Dylan’s writing into new areas (including No1 on Billboard) – and this on the verge of his eightieth year – is also astonishing. Mixing the modes of popular verse with his own telling twists of imagery and narrative, “Murder Most Foul” was at once a widescreen, mythological retelling of the Kennedy assassination, enveloped by a bird’s-eye, camera-obscura view of its impact on the day and in history, all wrapped up in a majestic, seemingly unending ‘king list’ of players, songs and singers, the list of names extending way before and after Kennedy’s death as if to suggest some kind of immortal flow through 20th-century popular music’s Elysium Fields. Against a circling, filigree piano accompaniment and delicate touches of cello and bass, and recorded so that you can all but feel the air in the room, Dylan’s voice and lyric does all sorts of things with time, combining the linear progress of the murder ballad with the circular time of the king list-cum playlist.

Two more songs have since been released, “I Contain Multitudes”, and “False Prophet”. Both have a lot to unpack, and turn out to be bigger on the inside than the outside. “Multitudes”, especially, brushes through a plethora of places, characters and times, and as the first song on Rough and Rowdy Ways, opens the door onto one of the strangest, strongest and plain weirdest of all Dylan’s albums. It’s a first-person song, but the ‘I’ has never felt less individual, packed as it is with the inner multitudes of experience, age, persona, projection, association and shared culture.

And so it is throughout this magnificent album, where the first person singular is a fractured entity, blown open wide, what’s left alive comprising a procession of tiny figures in huge landscapes, cityscapes, timescapes. There’s not a lot of shade in these songs. They stand in direct heat and light, exposed to the elements and tooled up with a striking arsenal of weaponry. At times I feel the influence of Western Lands-era William Burroughs, not that Dylan’s taking from him so much as expanding on the principles and the results of Burroughs’ methods, embedding them in the structure of the songs.

As serene as the surface of the music often is, there’s a restless and protean poetry broiling down below, embracing multitudes and leaving plenty of loose ends to tease out and chew over.

“False Prophet” carries Dylan’s heavily barked voice on a slow march, a beat as heavy as nails being hammered into a coffin. The lyrics are a bragging, proclaiming blizzard of end-time tableaux, pulled up in the songwriter’s nets and slopped out without any of the rules of time to separate them, the imagery slipping between Iron Age and classic film noir, peopled by the folk and blues traditions’ stock company of players and settings.

“My Own Version of You” is a gentle, funny, creepy, evocative – a weird Frankenstein-meets-Reanimator tale, set to a descending spiral staircase of a rhythm, at times with some of the spirit of Oh Mercy’s “Man In The Long Black Coat”. The opening lines are darkly funny, and brilliantly delivered: “All through the summer into January, I’ve been visiting morgues and monasteries, looking for the necessary body parts, limbs and livers and brains and hearts.” It’s hardly a Valentine’s, and its later verses take in Scarface and Rambo and even slavery in the ancient world (“Stand over there by the cypress tree, where the Trojan women were sold into slavery, long before the first Crusade, way back before England or America were made”). Verse after great verse lead off at tangents into who knows where before returning to the shifting chorus – “I’ll bring someone to life, use all of my powers, do it in the dark, in the wee small hours...” It’s a genius song that roams far but holds tight.

Similarly, “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself To You” is sung gorgeously, captured perfectly, played subtly, and set up on a circling vocal chorus. This slow, stately ballad breathes in all those Sinatra songs from the past few years and breathes out new and strange, Dylan playing with the mores of sentimental verse like a cat plays with its prey. It’s a song of devotion, but not necessarily devotion to any human object of affection, but to something otherworldly, the worlds of death and the Elysium Fields, or as Dylan calls it on the album’s last track, Key West.

But before we get there, meet “The Black Rider”, a song possibly drawing from the play of the same name by William Burroughs, Tom Waits and Robert Wilson, in which Marianne Faithfull starred as The Devil. It’s a song that seems to circle around the figure of death, for sure, its wagons hitched up to all the fleeting and ruling passions emptying out of life – rage, love, suffering, fortitude, fear. It’s beautifully spare in instrumentation – one of the few Dylan band recordings without a drummer – and hauntingly sung.

Cranking it up as the Black Rider departs is a raucous tribute to legendary bluesman Jimmy Reed, a Highway 61-style rocker in which the singer finds a creed in the music of the great man. Along the way, there’s plenty of arresting, crackling, lascivious, vampiric verses to trample through – “Transparent woman in a transparent dress, suits you well I must confess, I’ll break open your grapes and suck out your juice, I need you like a head needs a noose.”

“Mother of Muses” like “Black Rider”, and “Multitudes” are the only band tracks I know of Dylan’s that don’t feature a drummer. It’s spare and skeletal, slow and stately, its arrangement leaving plenty of air and space in the song, which adds to its profound sense of timelessness. The lyrics are steeped in classical mythology – nymphs of the forest, women of the chorus, a plea to Calliope, the patron of epic poetry. “Take me to the river and release its charms,” he croons, “Let me lay down a while in your sweet loving arms.” He sings, too, of Sherman, Patton and co, the American generals who, for Dylan or at least for this song, “laid the path for Presley to sing, who carved the path for Martin Luther King”. Subjects of epic verse, and epic history, for sure.

“Crossing The Rubicon” features the album’s big burst of harmonica, alongside a blow or two between verses in “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, cranking up to become another highlight, ranking with ease with the best of his work. Dylan is at his mercurial best here, at his own pace but as fast a gun as you ever saw, declaiming vivid tableaux over a blues steeped in the blood of the ancients, the heroes of Homer’s and Julius Caesar slitting the throats of their foe. Over seven and half glorious minutes, verses return again and again to that point of no return, and all the irreversible ways of getting there, and crossing the Rubicon.

Which brings us, in the end, to “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”, the first disc’s final song (“Murder Most Foul” stands alone on the second), and its longest, at nine-and-a-half minutes. It’s carried on a soft, see-sawing, wave-like riff overlaid by the welcome sound of an accordion, it’s atmospherics summoning up an American road trip into the Elysium Fields, its climate of endless summer casting dark shadows over the brightness and heat. The likes of Hemingway, Tennessee Williams and Shel Silverstein once found homes here. Maybe Dylan has a home there too. Maybe he’s got some real estate he wants to boost, because he sure makes Key West sound welcoming. It’s casual, metaphysical, full of detail, wonderfully sung – I heard touches of Blood on the Tracks and even Nashville Skyline rise out of the music here and there – with Dylan the lyricist making his spring-heeled way through a plethora of times, faces and places, all returning to roost on that two-word sign, Key West.

What to make of it? It’s a masterpiece. Even after many listens, it feels endless and bottomless. What a piece of work. It’s bizarre, eccentric, unlike anything else he or anyone else has done. It ranks with the very best of his work. Entropy is meant to be the third universal law, so for a 79-year-old artist to produce a work of such expansiveness, humanity and mystery – well that might be the greatest mystery of all.

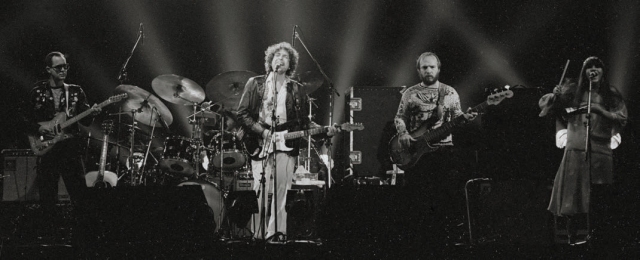

Bob Dylan’s audience at the Royal Albert Hall, 27 November, 2013

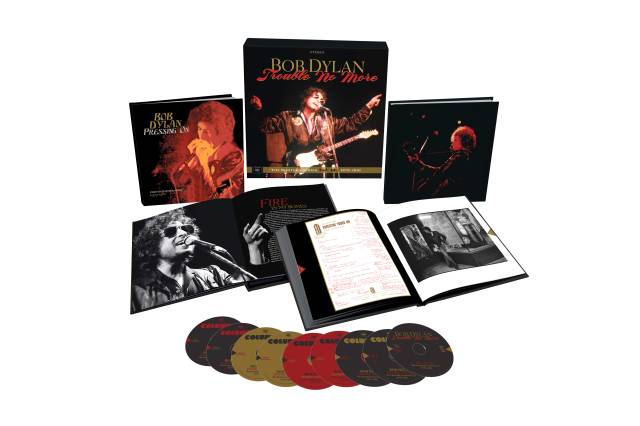

The Toronto recordings [which feature on the deluxe set and on the Trouble In Mind film] were spread over several days, with three cameras. It was a big thing that we were going to do this, and then no one heard anything more about it. They sat on a shelf for years, and now they’ve put it out. They have really done a good job editing it, and it’s just fantastic, the sound and the close-ups are really good.

The Toronto recordings [which feature on the deluxe set and on the Trouble In Mind film] were spread over several days, with three cameras. It was a big thing that we were going to do this, and then no one heard anything more about it. They sat on a shelf for years, and now they’ve put it out. They have really done a good job editing it, and it’s just fantastic, the sound and the close-ups are really good. from Jerry Garcia to Maria Muldaur and Mike Bloomfield, all these people came and sat in with us. It was exciting being in the same spot for a couple of weeks. But the newspapers – one review was headlined, God-Awful Dylan. Most of the press was so bad, Bob told me once he called up one of the reviewers, got his number, and called him on the phone, and when his wife answered and he could hear the sound of children in the background, he was so shocked that this dude would have a wife and family that he was speechless and hung up. [laughter] Like, what in the world are you writing about me, man, and then thinking, my God this guy’s got a wife and kids… I don’t even know what to say.

from Jerry Garcia to Maria Muldaur and Mike Bloomfield, all these people came and sat in with us. It was exciting being in the same spot for a couple of weeks. But the newspapers – one review was headlined, God-Awful Dylan. Most of the press was so bad, Bob told me once he called up one of the reviewers, got his number, and called him on the phone, and when his wife answered and he could hear the sound of children in the background, he was so shocked that this dude would have a wife and family that he was speechless and hung up. [laughter] Like, what in the world are you writing about me, man, and then thinking, my God this guy’s got a wife and kids… I don’t even know what to say. We’d rehearse all those songs in Bob’s studio, and Every Grain of Sand was really informal. Everyone had taken a break and gone off, to do whatever they were doing, and Bob and I and Jennifer Warnes were standing around the studio, and Bob started playing guitar. I started playing along with him, and they sang. It was very informal, and it came out really great. Caribbean Wind was a funny incident, I don’t know what versions they have on the boxed set but we got a call from Jimmy Iovine, one of these guys who thought, if I could just get Bob in the studio with the A-team guys, and really do a good basic track, all that stuff. ‘It’ll be huge, it’ll be great’. So he got all of us down early to Studio 55, an old studio that they had redone. An A-team LA pop music studio of 1981. He put me and Dave Mansfield in a room at the back. I had mandolin, Dave was on fiddle, and they had Jim boxed in with baffles and all this stuff, everything separated, everything discrete, and eventually Bob shows up with his guy, whoever was helping him out at the time, running errands and things, and he’s standing there, and they start telling him, Hey Bob this studio is where they cut White Christmas, because Bob loves old studios and is always looking for old studios and mics and stuff, and then they play this track of Caribbean Wind that they want Bob to sing over, and he stands there and listens to it straight-faced, waits until it finishes, and turns to his guy and he says, go get me the music for White Christmas because I can’t cut any of my music in here. [laughter]

We’d rehearse all those songs in Bob’s studio, and Every Grain of Sand was really informal. Everyone had taken a break and gone off, to do whatever they were doing, and Bob and I and Jennifer Warnes were standing around the studio, and Bob started playing guitar. I started playing along with him, and they sang. It was very informal, and it came out really great. Caribbean Wind was a funny incident, I don’t know what versions they have on the boxed set but we got a call from Jimmy Iovine, one of these guys who thought, if I could just get Bob in the studio with the A-team guys, and really do a good basic track, all that stuff. ‘It’ll be huge, it’ll be great’. So he got all of us down early to Studio 55, an old studio that they had redone. An A-team LA pop music studio of 1981. He put me and Dave Mansfield in a room at the back. I had mandolin, Dave was on fiddle, and they had Jim boxed in with baffles and all this stuff, everything separated, everything discrete, and eventually Bob shows up with his guy, whoever was helping him out at the time, running errands and things, and he’s standing there, and they start telling him, Hey Bob this studio is where they cut White Christmas, because Bob loves old studios and is always looking for old studios and mics and stuff, and then they play this track of Caribbean Wind that they want Bob to sing over, and he stands there and listens to it straight-faced, waits until it finishes, and turns to his guy and he says, go get me the music for White Christmas because I can’t cut any of my music in here. [laughter] I really love Pressing On, from Saved. That is very funky, one of the funkiest things we ever did. I like that one a lot. Every Grain of Sand is another of my favourites, because it came down so naturally, but then all of them came down pretty naturally. I think we’d played most of the other songs a lot on the road, so they were a little more worked out. That’s always the thing Bob tried to avoid. He wanted to stop people getting a part that they’ll play every night, which tends to happen. You find something that works and you stick with it and the next thing you know you have this set- in-stone arrangement. Pressing On was more spontaneous, because I don’t remember us playing it as much as we did the other songs, like Saved. Now Saved is pretty great, especially when you hear these new live mixes. And Solid Rock, that’s a really good one.

I really love Pressing On, from Saved. That is very funky, one of the funkiest things we ever did. I like that one a lot. Every Grain of Sand is another of my favourites, because it came down so naturally, but then all of them came down pretty naturally. I think we’d played most of the other songs a lot on the road, so they were a little more worked out. That’s always the thing Bob tried to avoid. He wanted to stop people getting a part that they’ll play every night, which tends to happen. You find something that works and you stick with it and the next thing you know you have this set- in-stone arrangement. Pressing On was more spontaneous, because I don’t remember us playing it as much as we did the other songs, like Saved. Now Saved is pretty great, especially when you hear these new live mixes. And Solid Rock, that’s a really good one.