Mark E Smith Interview Malmaison Hotel Bar, Manchester, 14 May 2004

Herein, the late great leader of The Fall discusses the group, the-then new album, Country on the Click, touring the US, William Burroughs, Orson Welles, Brion Gysin, TOTP albums from the 1970s, analog synths, group members, poetry and spoken word, Hex Induction, the nature of composition, production, record companies, reissues, Arthur Machen, Hawkwind and, well, a hell of a lot more. Engage and enjoy, salute a master

Mark Smith walks carefully down the sloping ramp from the hotel reception into the bar, head turned to spot the likely journalist among the room’s dozen or so post-lunch hour drinkers. Hotel bar with waiter service, Becks on tap, smoking all areas. We move to a table bear the wall, and Mark settles into a chair and puts his crutches against the wall next to him. ‘I’m gonna throw these as far as I can when I’ve finished with them,’ he says when I ask how he is. The long slog of an American tour, from New York through the Midwest to Texas, Arizona and California, has taken its toll, especially after giving up the medication, and its mind-deadening side-effects. Smith prefers to hear what the body is telling him; that it’s in pain. It also means that he can drink.

MES: Every interview in America that’s all they wanted to talk about. ‘What about the pain….’ [laughter]

Tim Cumming: How was the American tour?

MES: It was good, it was good. We came back two weeks early. We were going to have to cross the desert, and we didn’t want to do that. We were going to go back but I don’t think we can do that now. The visas run out next week. It’s got much harder in the last couple of years. We took some internal flights, and you’re not talking an hour or two, you’re talking four hours to get through an hour’s plane journey. The places we were in weren’t used to it. Places like St Louis had never done a security operation. You get these old fellas saying, I think you’re supposed to sit down now. I’m supposed to get this thing out and wave it like this. It’s quite weird.

TC: Weren’t you there a couple of years ago?

MES: We were there last year and yeah, the year before too.

TC: How much do you think it’s changed, and how much do you travel around?

MES: I insist on doing out of the way places. I insist on doing Texas and places like that. Doesn’t go down very well with people in New York much. We’ve got fanatics, fanatical fans in the mid west. With The Fall it’s quite peculiar. A lot of British groups don’t do so well in Chicago and places like that. We do, you know. So if you’re going to go, you might as well do those places. So we did it, and places like Pittsburgh, where nobody goes anymore.

TC: What kind of venues where you playing?

MES: We were drawing all kinds of ages, which was interesting. Anyone from 12 to 80. You get a lot of young kids there, which is good. Quite fanatical, about 16.

TC: There’s always been that renewal in the group and the audience.

MES: Yeah [laughter] Not the usual lot like me and you. Have you been working for this lot [the Independent newspaper] long?

TC: I’m freelance. Done it for about four years. First one I did was on Stockhausen. I did one on Orson Welles, and this film that never came out called The Other Side of the Wind.

MES: A mate of mine says he’s got that on video. He’s had it for ages. I’m a big fan of his. His Macbeth is the best one ever, that [laughter]. Really good. There’s those bits where his hair’s five times longer because they had to shoot it three months later.

TC: I saw F for Fake in the cinema not long ago.

MES: F for Fake’s a great one. A very good film. Way ahead of its time. What’s The Other Side of the Wind about? My mate keeps going on about it.

TC: John Huston plays an old Hollywood director, coming back with one last film, a kind of sex and occult movie, and there’s this party and screening of bits of the movie in a movie, and all these young directors like Bogdanovich and Curtis Harrington, playing kind of acolytes.

MES: Is it coming out then?

TC: They need two or three million to finish off the editing and stuff.[pause: 2017 update, we are still waiting, but now Netflix is on board] I’m going to writing about the new Best Of CD, 50,000 Fall Fans Can’t Be Wrong. Did you have much involvement in it?

MES: I did with that one, yeah. Not a lot of them I don’t, but Sanctuary is alright actually. They do sort of put it past me.

TC: Did you have your own choice of tracks?

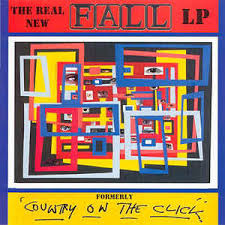

MES: They always try it on and you’ve got to chase them up. I think it was a lot longer, that. A three-CD one and all that. There’s only so much you can put out, I think. The last one’s more important to me, The Real New Fall LP. I think it’s good, that. The American copy’s good as well. It’s got a few different tracks on it, and it’s got a much sharper cut for some reason. harder. The same mix but very hard.

TC: What was the story about the making of the album? I heard it was recorded in a week then held back for about a year?

MES: Well, about six months of pissing around with it. We did it and I was very happy with it, and then the record company – Action – started messing around with it. So I went to EMI and they started messing around with it, which was the only reason I went there in the first place. And I went to Mute, and they started pissing around. So I just went back to Action. Did a lot of it again, to be honest. Which I’ve never had to do before. So it’s absolutely what I want now.

TC: The re-recording or the mixing?

MES: Well, it’s funny, it’s sort of remixing but it’s more or les what it was in the first place. I couldn’t really believe after all this time that people started thinking they could take tracks away of mine and mess about with them. It’s forbidden. So that’s exactly how it should sound.

TC: The American release has a couple of remixes and a new track, is that it?

MES: Yeah. Worth hearing though.

TC: With the album being recorded so quickly, was working on the songs beforehand a much longer process? You’re working with a very new band.

MES: Yeah [long pause] I didn’t have any problems with em. That’s what annoyed me. It’s like if you make it look a bit too easy, people think they can just fiddle around with it. It was hard work, but something like Sparta was knocked up in two days. It sounded really great. Then you get it back and it sounded like Posh Spice, you know. So that got me off, of course. Putting on extra vocals and all that. Nowadays they’ve got too much equipment. You know, it’s out of time. It’s very out of date, trying to put dance music on top of rock. It’s been done. We never needed dance stuff over out stuff. There’s always been that element there. Our kind of stuff is atonal, and they’re trying to put dancy tunes over it, so it skews the whole track. I hate talking like this because you get into studio speak, you know.

TC: Do you like doing stuff in the studio or is it better live?

MES: They’re both alright. The thing about the studio is you have to hang around a lot. It’s a pain in the arse really. You go out for an hour and come back and they’re still messing around.

TC: Most of the time is spending time?

MES: Yeah, worth it though.

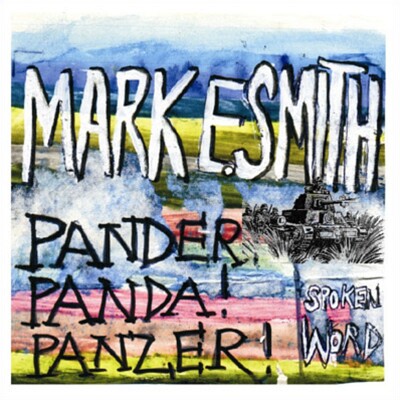

TC: With songs like Last Words, there’s that thing where you change sound sources, and you do that a lot on Panda Pander Panzer, and it’s something that goes way back.

MES: Yeah. [pause] It’s quite interesting about all this equipment and what they don’t do with it. It’s funny doing the tour with these [gestures to crutches] because I’ve had to do most of it sitting down. Singing sat down the whole time.

TC: Are all the spoken word performances sat down?

MES: Yeah well it’s held me in good stead really. I’m settled in like with one mic going through an amp, another going through the desk, and through another amp. Good one, that.

TC: Three different sources?

MES: Yeah.

TC: What’s the attraction of using all these different sound sources? Is it how you think about sound?

MES: Yeah, very much so. But I haven’t got a musician’s ear, me, at all. I know less now that I did when I started. Chord progressions and things. Cos the group now are quite sticklers for the music. They’re all a generation younger than me. Where I’m coming from has always been atonal and quite savage. So I get them to unplay a bit [laughter].

TC: So they come to you with something, with a song, and then play it through.

MES: I rough it up, yeah. Lop bits off it. Don’t need that bit [laughter]. Put this bit in [laughter].

TC: And that’s the process of making a Fall song?

MES: Aaah, I suppose so, yeah. I don’t think too much about it really.

TC: You don’t reflect on it or intellectualise it in a certain way?

MES: I try to but, um, I think it’s important for the group to be topical, not in a sound way, but in a sort of musical way.

TC: Do you find yourself subtracting more than adding things?

MES: More so, more so, yeah. Savage edits now, you know. I’m really into them. Cutting whole chunks out of the song. Which you have to fight for. It’s the opposite of being a writer.

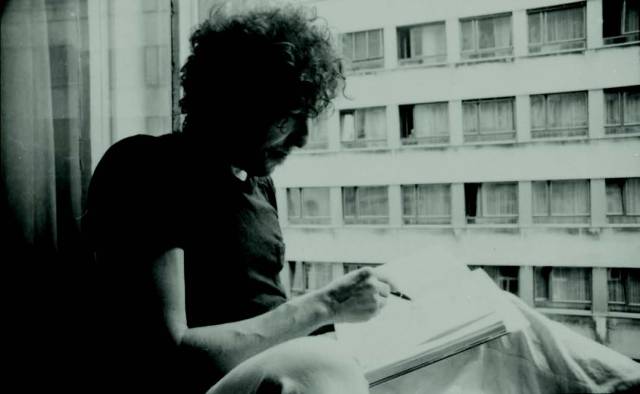

TC: How much writing do you do on a regular basis?

MES: Depends on what I’m doing. I still write every day. It’s not as voluminous as it used to be.

TC: Do you find yourself writing a lot on tour?

MES: Yeah. I’m hoping to put June apart for recording.

TC: Will you have Dingo back?

MES: I have no idea. I don’t know, I’m quite happy with this new lot. He’s good. I also found out on tour he’s quite a little genius himself. He’s been writing for years apparently, since he was about 15. Very interesting stuff. Sort of like Manc pop but a bit weird. So I’m hoping to use a bit of his stuff actually. Different angles. What kind of music do you like.

TC: A lot of country and western, Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, Townes van Zandt. Rock n roll stuff.

MES: I bought a Merle Haggard LP at a truck stop. Haven’t had time to play it yet. It was one of these bargain ones. I’ve been looking at it wanting to play it all the fucking time. The titles are great, you know. The Bottle and Me, and all that, you know.

TC: And German stuff – Neu, Ash Ra Tempel. I’ve got these recent CDs by Manuel Gottsching.

MES: Oh aye yeah. [examines CDs] Oh they are good. I’ve got some of this somewhere. Have you heard of Mouse on Mars? Sort of German poppy group. I saw them in London and they were fantastic. They were really like Neu! With like synths. Nothing like their records. The records are all – bippity bop. There’s supposed to be a compilation LP out of Fall songs by all these groups.

TC: I’ve got a copy. Perverted by Mark E Smith.

MES: What’s it like, is it good?

TC: Yeah, really good. [pause] You’ve got links with Germany going back to that book of lyrics that came out in the mid 80s.

MES: Yeah. The wife was brought up in Germany. She’s playing in the group now. It’s good. People like it. Bit of drive to it.

TC: In Country on the Click, there’s quite a lot of electronic things going on, but in recent gigs it’s been much more a straight guitar-drum-bass sound.

MES: I’ve been trying to get round to that. In America we were working on it a lot. By the time we’d finished there, electronics was a lot more prevalent than say the last time you saw us.

TC: Using sequencers, stuff like that?

MES: Well, Elena’s got a lot of old synthesisers she brought back from Berlin, and it’s really good, the sound, like nothing I’ve ever heard. It’s quite funny, all that stuff you used to throw out fifteen years ago is all coming back now.

TC: Like those 80s pad drums are coming back.

MES: Good. I used to like them. We used to have them in The Fall when we started out. People used to laugh. They were good.

TC: Mate of mine remembers seeing the band in 79 when Una Baines was using an ironing board as a keyboard stand.

MES: Right, yeah. You’d put magnetic mikes on the ironing board. Can’t get them anymore. All that’s like gold dust now.

TC: Do you like playing around with that kind of equipment?

MES: Yeah. I do a lot of that on stage. I have to be very careful, because musicians have a temper, you know. Turning the dial in the middle of stuff, breaking things you shouldn’t. I’d say about a tenth of the money we made – if we made any in America – was spent on microphones and amplifiers. Mikes I dropped or gave to the audience. They don’t take that kind of thing very lightly over there. Like [American accent] ‘that mike was made in San Francisco in 1969…’ Right. ‘You gave it to the audience and we’ve not seen it again.’ Sorry and all that, you know. $500. [laughter]

TC: This 50,000 Fall Fans… is a 25th anniversary compilation?

MES: Yeah well I’m very wary of all that stuff.

TC: You don’t want to be in a position to have to consider all that?

MES: Well I never have, y’know. [Looks through the track list] My eyes sort of run out half way down it. I’m sure it’s good, you know. That’s the good thing about Sanctuary. They have got a bit of taste. Some of the other compilations, I used to have nightmares about them.

TC: Have you been involved in the Sanctuary reissues project?

MES: Well I think they’re alright, you know. At least they’re mastered properly. What I don’t like is the way they don’t have any kind of theme. Especially with CDs. It’s like they haven’t really got their heads around the CD. I still think in LP form.

TC: Do you think in LP time as well?

MES: Yeah, like a thread going through it. I sort of got around that with Country on the Click because you can really listen to it all the way through as if it were an LP. With a lot of compilations you have to stick a lot of extra tracks on and they jut out.

TC: With Country on the Click, when you were putting it together, do you have an intuition about running order?

MES: Very much, yeah. You still get it wrong, no matter what you say. [picks up CotC] Even that’s in the wrong bloody order. They switched them around. So it’s in the right order now, the American one.

TC: Sparta’s going to be a single here, right?

MES: That’s what I found out when I got home. I wanted to put this song Portugal on the B Side, which we put on the American thing. And they were going, no, no you can’t do it, it’s libellous. Last time we played in Portugal there was this road crew. It’s completely surreal. We arrived and they sort of pissed off on the day of the show, saying we behaved really badly and all this. Somebody threw a bit of paper at them, like a plane or something. It was quite funny; they wrote, like, their excuses for running off. But if you saw these blokes you’d laugh your head off, because they were four big blokes with long hair and leather jackets, and like, I’d knocked on the door at 12 o clock at night to ask what time they’re going down to the show. Just banging on the door. And they wrote, ‘he was banging on our door at 12 o clock at night,’ and I got the group to read all their letters out. And a few more. It’s a good track. I’m quite mad they didn’t put it on the B-side. It would’ve fitted great, Sparta with Portugal. It would’ve been good.

TC: Can you remember how a song like Sparta come about? It’s a really great track.

MES: Everybody likes it, yeah. The group made this song that was sort of like Born to Be Wild, I thought, with a great feel to it. And Elena came up with some great words and I added some words I thought were like the Greek football fan’s attitude, you know. I do know quite a few Greek football fans, and their attitude to soccer is completely different to Britain. Sort of cobbled it all together, put a Greek motif on the guitar and that was it.

TC: The lyrics seem to be a springboard form whatever interpretation you want to put on it.

MES: Right. The thing is, their mental attitude is quite strange. It’s not about winning or anything. It’s just about being within the club. They find British fans very funny. They find them hilarious. You know, when they cry. You see it now, you know. They cry when they don’t win, and all that.

TC: I saw that the other day with the Chelsea game.

MES: Yeah!

TC: A bit shameful.

MES: [much laughter] Spartans, you know, Greeks don’t even want to know the score, they just want to get to the match. [laughter] It’s not really important, it’s not really a matter of life and death. I don’t think anyone else has got the set up we’ve got here. It was easier to get results for Man City in America than it is to get them here. I find it funny that you have to pay to watch England, or go to a pub to watch it.

TC: A kind of pay per view culture.

MES: Like, what credit card have you got? Quite horrid.

TC: With a lot of your songs, they seem to be open to interpretation of anyone who hears them. Is that what you want, basically?

MES: I’m glad you’ve said that, yeah.

TC: And when you’re performing, how do you approach the songs?

MES: It’s more open-handed now. As I said on that last American tour my voice was getting really good, and a lot of the songs sounded better live. I can ease in new material.

TC: You were introducing new material?

MES: Trying to, yeah. We always have this fight, you know, with musicians. They’d like to do the same set forever, for like fifteen years. [points to Best-Of CD] They’d do this set if they could, a lot of the musicians I’ve worked with.

TC: That Blackburn DVD came out and that is basically this set, isn’t it?

MES: Yeah that’s right.

TC: Was that done specifically for the DVD?

MES: Yeah, I’m quite pleased with that. I can’t watch myself you see. Telly or video or anything like that. It doesn’t make any sense to me, but I was pleased with that one. It was a three-day project. They wanted to do some old songs, and there were three or four we’d never even think of doing. And it was for this record company that used to do all these duff compilations. [laughter] Secret Records. Used to be Trojan. Brought out all these horrible compilations that didn’t make any sense. All crap. Not that the music’s crap, it’s just the way it’s cobbled together. Makes no sense.

TC: Will the Sanctuary Reissues continue, and will you try and phase out the old stuff?

MES: Correct, yeah. Do a big clear-up and get it out the way. Sanctuary are good like that. They’re doing it all over the shop. They’re doing it with Deep Purple. They’re doing it a bit tasteful. You can draw a line under it, you know.

TC: They were doing the same thing with Hawkwind.

MES [much laughter] They’re having a resurgence in America. Kids we were talking to were obsessed with them. I saw Hawkwind when I was about fucking 16. Status Quo were supporting them. This was when Silver Machine were in the charts. They came on and did a 25 minute song that made so sense. It was brilliant.

TC: They’re still doing it now. I saw them at Concord 2 in Brighton about two weeks ago.

MES: You’re joking aren’t you? I’m talking about when Lemmy was in them.

TC: There’s been a few Bob Calvert albums being re-released.

MES: Yeah, they’re really good. He used to hang around with Moorcock, didn’t he? In fact I think Moorcock used a lot of his stuff.

TC: When you were starting out, what were the people you were listening to – your frames of reference seem wider than a lot of other bands. People like John cage as much as Can.

MES: Rock music is so standardised these days, I can’t believe it really. It’s overmixed. If you’re going to do basic rock, you’ve got to do it properly. You shouldn’t interfere with about eight guitar overdubs. It’s wrong isn’t it.

TC: Do you think there’s a purity in the essential form – bass, drums, guitar.

MES: Sure, sure. I still think the same I’ve always thought, that the guitar’s not been used properly yet. I might have to go back to playing it again.

TC: When did you last play?

MES: Well only for composition. Around Hex Induction Hour, used to play a lot of guitar. I do like that one. It’s the only one I like from the 80s. In fact we do Mere Pseud Mag. It always sounds good. Did a version in Texas three days before we came home, and did the end bit, repeating the line for about five minutes. It was good. Like, ‘oh, his medication’s kicked in.’ No it hasn’t. It’s fucking great, you know.

TC: It makes it a sort of invocation.

MES: Yeah. People don’t do that much no more.

TC: Now they keep it like the LP is.

MES: Straighter now than ever, don’t you think?

TC: What, these days?

MES: Yeah

TC: Is there anyone new you’ve got your eye on?

MES: I don’t get the time, you know, Tim. I do like a lot of that Kraut stuff that I’ve heard, though I can’t remember the names or anything. In America we were getting a lot of these tapes off groups. It’s dire stuff. Really bad. It’s like this semi-grunge movement’s out there. And this Strokes-type sound which I hate. Bad 70s music.

TC: Three Dog Night sort of thing.

MES: I think so. They’re even doing this travesty tomorrow. The Eurovision Song Contest. I mean, how dare they tamper with that. I’m a big fan., me. They’re doing all these things where they’re turning it into Pop Idol. The British entry and the German entry really does sound like Three Dog Night. That’s exactly it. It sounds like what their fathers listened to. 3 Dog Night crossed with Joe Cocker or something. Horrible. The theory of Eurovision was that it was totally amateurish. Tripe. You get good stuff. But now they’re playing so there’s a quarter final. It’s a bit like the Champions league, they eliminated some countries last night, so it won’t be all of Europe in it.

TC: We did well last year.

MES: That was a bit of a triumph, wasn’t it? That was a great one, that one.

TC: Would you like to use that poppy kind of sound?

MES: Always thought I was doing that.

TC: Five or six years back, you had Britpop, which was very retrospective, referential, 60s and 70s stuff.

MES: I think these things show a bit of a gap, a yearning for something. Hence an interest in all this stuff [gestures to 50,00 Fall Fans…] shows there’s something wrong. I’ve said it before, but you meet a lot of these groups now and it’s like going to a bloody businessman’s convention. Working out what their investments are going to be, what they’re gonna be doing in three years. It more than takes the fun out of it.

TC: Do you still have fun with it? You’ve worked outside the mainstream for 25 years. How is it now?

MES: I think I’m alright. I don’t look at it like that. Am I making any sense here, Tim?

TC: You look at it more as a circular thing without a linear time line?

MES: I think so, very much. I call it the seven year gap. There’s a Fall time and there isn’t. If you wrote a graph of The Fall it would go up and down like this, like the Alps.

TC: At the beginning, were avant-garde people like Stockhausen and Burroughs an influence?

MES: Yeah, that’s right, when we started out. I still like Nothing Here But the Recordings by William Burroughs. It’s really good. It’s something that Genesis P Orridge put out. A bit of an influence that, I must say. Genesis has made a bit of a comeback, have you heard about that?

TC: I heard about getting his lips and tits done.

MES: I know about that. Don’t want to think about it. If anyone’s going to rebuild themselves it’s going to be someone like that. They used this binary head thing, some kind of recording device. I used it on a track once. They did a show at the Hacienda where they tried to put it through a stereo, through the PA rather. The fact they were playing hardly anything didn’t seem to bother them. It was quite interesting.

TC: When I saw Psychic TV in the mid 80s there seemed to be hardly anyone playing, it was all tapes, and a dozen guys on stage.

MES: You can hear the guitar going on in the background, ding-ding-ding-ding-ding,. And Genesis in the middle, or wandering around the audience. Like being in the middle of a bad dream.

TC: I interviewed Genesis about Brion Gysin, and he talked about how he rescued all these films with Burroughs and Anthony Balch.

MES: He’s good like that, Genesis. He’s very good that way.

TC: Do you do any videos these days?

MES: I can’t be doing with them. It’s the same thing with sound. You have to really argue with them. It’s a bit Orson Welles-ish. Looking at that Blackburn DVD, though, we put some daft staged pre-show thing which I did at the end of it, in a holiday camp. It was dead funny actually. It started as a Channel 4 documentary which didn’t come out. The usual stuff. That was funny, because I said alright to the group and they were in and out so they weren’t really in on it. Like, that’s not going in the set you know, and getting them to write out the set list again. It’s really good. That’s the sort of thing I like. In this culture, you watch a film then see all the blokes up ladders and all that. It’s like the crew getting more attention. You get all these programmes on, like the top 50 films and you get Citizen Kane on, and you get about ten seconds of it and this guy starts talking about it. I find that really irritating.

TC: You don’t get to eat anything, you just get to see the dish.

MES: [laughter] That’s very well put.

TC: I’ve got this great BBC video of Orson Welles talking for about three hours. One camera angle.

MES: I’ve got that. It’s good isn’t it. He’s got his cigar and all that. Great to watch.

TC: After doing that Blackburn DVD, did you think of bringing in more old songs?

MES: Sort of, yeah. In my mind it’s a long time ago, though it isn’t that long ago.

TC: Do you avoid doing it because you don’t want the audience to expect it?

MES: Yeah, I’m kind of tight on that, Tim. I don’t mind this stuff [the CD and DVD] but I don’t want too many live show like that. I always think it’ll stop people coming. The show’s completely different now though.

TC: Did you get any trouble from cancelling the last few shows? Was it a band decision about not wanting to go on, or more to do with the pain?

MES: I don’t know. You’re talking about that Fallnet aren’t you? I think that Fallnet has to be tightened up a bit, actually. It’s getting too much like a chat room, in my opinion. I’m going to tighten up on that, don’t you worry. I never read it, but when I was in America I had a look at it. Most of it’s alright, but I don’t like all that ‘I paid so and so…’ This culture where you have to explain everything all the time what you’re doing. It puts a clamp on you. The people who are into the Fall don’t really care about them things. You get all these old fogies going I haven’t seen so and so since 1983. I had a lot of complaints from kids in their early 20s who want to go on Fallnet to find out what it is now, not what it was. They’ve already got the compilations, they don’t want to hear people talk about them. It can be quite a trap, I think.

TC: As a band site it’s really good.

MES: Oh yeah. It’s the envy of a lot of other groups, I know that.

TC: There was some rumour you appeared in the Bob Dylan movie, Masked and Anonymous.

MES: I heard that. Someone told me about that. Could be someone who looks like me. It’s fire in the hands of fools a lot of the time. Those times where they go, I saw Mark Smith the other day in Stoke. You get fellas pretending to be me, which I have to track down. Which I find a real pain in the arse.

TC: The German CD [Perverted By Mark E] has a song listing all the ex Fall members.

MES: [laughter] Fucking great. I’d love to hear that. I think I might know the people who did that.

TC: I’d like to ask about the making of Hex Induction Hour.

MES: It was done live in a cinema in Hitchin. Without an audience. This is the last LP I thought I’d ever do, so I wanted to get everything on it. So I packed it all in. It’s one of the ones – I don’t sit down and listen to it every week or anything – but I do give it a good hearing. It stands up, I think , which surprised me.

TC: When the remasters come out, will it have more original material, like the full half-hour cut of And This Day?

MES: No, you can’t alter that. All that stuff’s on the floor, thank god. They’ll put a couple of singles on it, with some good B sides.

TC: And some was recorded in Iceland?

MES: In a cave made out of lava. Hip Priest was done there. It was before the days when Iceland got hip. You go there now and the studios are all complexes. Then it was like a lava igloo. It’s why Hip Priest and the other ones sound good. It’s a very strange sound. We should’ve done more, really. I think it fell to bits a year later. The lava cracked.

TC: Hip Priest was used in Silence of the Lambs. Is that a good source of income?

MES: Not particularly. I was more democratic in those days and gave everyone a share so that it has to go round about six people. [laughter] Of course I wrote every note.

TC: I heard there was some screw-up over registering Touch Sensitive before it was used in the car advert.

MES: I think I forgot to register it. I don’t really worry about that. It’s quite funny, because if there’s one kind of advert I rail against it’s car adverts. The money they spend you could make a British film, and bugger me, I’m one of them.

TC: What do you think of the three books that came out last year?

MES: I liked the Users Guide, that was just LP by LP. Facts. I enjoyed that one. But the other one, Hip Priest, where he interviewed everyone but me. I didn’t like that at all. I didn’t read it. It’s amazing how he tracked down everybody but me. I deliberately didn’t talk to him, but I mean, I don’t really go there, Tim.

TC: You want to avoid having to look at it the way they look at it?

MES: Yeah. It sounds a bit precocious, but. Like a lot of things, it’s all through rose-tinted glasses. The bits I read in Hip Priest about what a great guy I am and all that, from ex members. That wasn’t the case at the time.

TC: Is there always tension between you and musicians?

MES: Very much, all the time. I don’t know what it is. Ever today, you know. I sort of lose me rag with them. You can say, well, ten years ago you were having hard times and all that, you were drinking a lot of whiskey, which I used to do, but now it’s still the same, sober or no.t Still, I think it works.

TC: It’s part of The Fall’s tension.

MES: I think so, too.

TC: It’s the creative tension between two very different attitudes.

MES: Very much so, yeah. I can’t do what they do and they can’t do what I do.

TC: When you’re bringing in a new member you’re basically trying them untried.

MES: I try to do it that way.

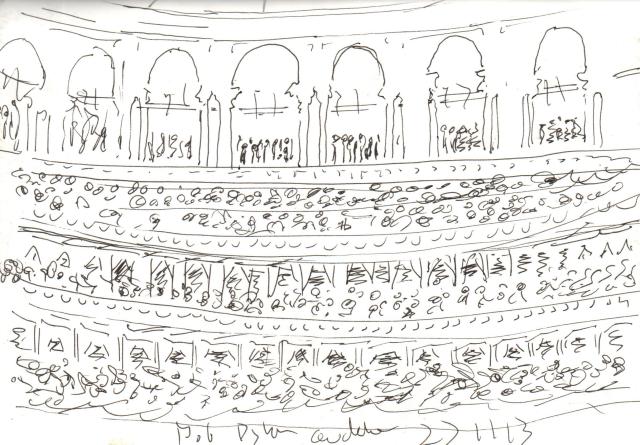

TC: Did you stay to watch the Magic Band when you played with them at the Royal Festival Hall?

MES: No I didn’t. I was a bit upset actually. I was very disappointed.

TC: Were you hoping to perform with them?

MES: That was touted, yeah, at this LA festival about six months before. The idea was to do the whole of Trout Mask Replica with different vocalists, which I thought was a really good idea. It’s one of the few albums where I know all the lyrics. There’s about five songs I can do just like that. What they played wasn’t really the Beefheart period I like, the seventies period. I liked the 60s stuff much better. But it’s up to them what they do.

TC: It was good, but it was an imitation, they were sort of their own tribute band. It was very different to how you’d do it.

MES: I’m not used to supporting people anymore [laughter]. That might have something to do with it.

TC: In writing songs, is it more to do with impact and tone than with telling a story?

MES: I do fancy going back to a bit of a storyline. A lot of material I keep for a few years, actually. I have it around in my head. I find that’s the best way.

TC: Do you find yourself writing on a theme?

MES: Yeah, you look back over a three-week period, there’s a thread there you couldn’t see. A lot of things that read like nonsense when you write them make a lot of sense a month later. Seems like complete rubbish as you’re writing it down, and it seems to come true in a couple of weeks.

TC: There’s well-known instances where your songs have come true.

MES: That’s very strange. Bombast, somebody played that in America, bombs coming down. Strange song. Don’t know where the hell they came from at the time.

TC: You were a big fan of Philip K Dick.

MES: Still am. A massive fan. I got the DVD of the movie Spielberg did, and he’s talking as if he wrote it himself. It’s all in the public domain, which is a big thing in America. It’s public property so they don’t have to pay anymore. The Spielberg one is only about 50 pages long, and the film’s really great, I think Tom Cruise is really good in it, but on the DVD he’s like explaining Dick’s work without mentioning Dick’s name at all. It’s very strange. It’s like you claiming to have written Country on the Click, you know what I mean? It’s something he talks about in his stories.

TC: I wondered of the song Book of Lies was a reference to Crowley, whether he’s a figure you’re interested in.

MES: Well I do, but I keep it at the end of my arm. I’ve seen too many people dabble in that shit, you know. Like Genesis, he was into all that wasn’t he. You’ve got to be very careful with that stuff. I do like his Tarot though, the Crowley one. I do still like that. The interpretations of the cards are so funny, some of them. The reverse one is like, you are a crawling cockroach of the worst order [laughter]. The normal one is, you’re blocked, you’re not doing the right thing, you should be a bit more open and think about what you want to do. And he says, you’re a crawling cockroach of the worst order. Hah! You are like a bluebottle in human form. Imagine reading that to somebody. They’d probably kill themselves. [laughter] You are an average person, you’ll never amount to anything. [more laughter]

TC: Do what thou wilt and those phrases.

MES: Oh that’s still good.

TC: During the Fall’s history, have you ever thought about knocking it on the head?

MES: About once a year. All the time, yeah.

TC: The way you are, do you have to keep out of the trap of the past, and try and just focus on the present?

MES: I try to yeah, but people don’t like – people aren’t as daft as you think. You can’t be expected to know every Fall LP and all that. I think that’s good. It’s like these compilations. You can’t do anything about it. I remember when I was a kid you’d buy this LP and it was a duff Kinks LP, you got it home and discovered it was all duff B sides. But you learnt something from it. At least it was there.

TC: I bought this rock n roll album when I was a kid, and it wasn’t by the originals at all, it was like one of those Top of the Pops albums.

MES: Oh they were great weren’t they? I used to buy loads of those. One of my favourite LPs has ‘hits of T Rex, Slade and The Sweet’. I remember buying it when I was about 15. And inside it’s got, ‘as performed by Unicorn…’ And they’re better than the originals. They’re a lot better. This bloke, his voice breaks in the middle, and with the siren on The Sweet, you know Blockbuster, the police siren gets really out of control. It’s fantastic.

TC: They didn’t have enough budget to change it.

MES: [laughter] A lot of them are better than the original, especially the Slade one. The blokes voice cracks, it goes in the middle of the song. It’s excellent.

TC: Did you like Glam Rock?

MES: No, not at all.

TC: Going back to Pander Panda Panzer, was it you who edited and put it together?

MES: Dingo helped me a lot on that.

TC: It has some beautiful ambient stuff coming in and out between the recordings.

MES: Yeah it’s really nice isn’t it. Good.

TC: You kept it to one track as well.

MES: Yeah. That confused a lot of people.

TC: Were the decisions made about what to put in done on the fly or with more conscious thought?

MES: No, I just wanted to get that out. The first spoken word was really popular and no one wanted to bring another one out. Action Records did that one. I listen to it. I like it. What I use it for sometimes is an outro tape for a show. Because I’m, always hearing things. You play these things in a show and go off and the DJs and people put on The Smiths, especially in small towns. So you shove that on and it shuts them all up. Empties the hall quick.

[Elena, Mark’s wife arrives]

TC: Have you thought about publishing stuff?

MES: Very much so, but I haven’t got the concentration.

[TC discusses his books Contact Print and Apocalypso from Wreckingball Press and Stride, as well as 80s-90s small mag culture of The Wide Skirt, Echo Room, Liar Republic, et al)

MES: Remember that thing you were reading in Baltimore, Elena? You get these free magazines.

ELENA: And all they write about is their childhood trauma, what’s been done to them.

MES: It’s really poor stuff. But these mags are really good. They bring them out in every city. A bit like City Life used to be. They had these poetry sections, and you read them, bloody hell. Bad, bad. Really.

TC: It doesn’t get out of the box of the personal.

MES: My grandmother…

TC: I think it’s workshop culture, actually. Perpetrating it. Write what you know culture.

MES: I did this spoken word in Sweden.

ELENA: With the American woman.

MES: It was in the afternoon. It was a nice festival, in this Swedish palace with chandeliers. People took it dead serious. Half of them were in suits. It was the afternoon and we were going to play at nine and I wanted to do a sound check. I said I was only gonna do 20 minutes anyway, at about 4pm. So we get there, me and the roadie, and it’s about 3 o clock and this woman’s going on. The microphone’s on, me tape’s ready, I’m a bit nervous because I’m on my own, the group’s not there. And, uh, this woman goes on at three, and it’s a quarter to five and she’s still on, like ‘I remember the red bouncing ball…’ It was a red bouncing ball. It was like Friends, you know what I mean?

TC: Without the laughs.

MES: Yeah [laughter] So we were saying get off! Get off! Get off! Yelling from the balcony. So I went on for five minutes.

TC: When I’m doing a reading I wouldn’t do more than 15 minutes.

Elena: It’s the attention span.

TC: No you can’t do more than that.

MES: 25 is my maximum.

TC: Do you think you’ll end up doing more of that? There was one in Manchester recently with John Cooper Clark.

MES: That was very good actually. But it’s the same thing; read five minutes, then it’s an hour before anyone else went on. I was in my wheelchair so I couldn’t get out of the building.

TC: With readings, and songs, do you improvise, so that something strikes you and you think – that’ll work?

MES: Touch wood it usually does, yes. So far. I’ve never had a prolonged feeling of plodding on in the studio, and nothing’s going anywhere. That’s good. It did happen about ten years ago, around Light User Syndrome. I was really stuck sometimes, to be honest.

TC: Is that why the band disappeared in 98?

MES: That’s right. Correct. That’s true. Well spotted. The group’s good, but not sparking anything off. And of course you’re running up bills in the studio, it’s London.

TC: Do you try and operate it so you own the masters and tout them?

MES: Only with the new one.

TC: I heard Dingo had a studio you could record in.

MES: Yeah. Let’s hope he’s still got it when he comes back of loan. It’s a bloody footballing term, isn’t it. Like a transfer.

TC: When do you think another LP will be out?

MES: By November. I don’t usually tell people these things, Tim. It’s good that you asked. The group will read it in The Independent and feel more secure.

TC: I did one earlier in the year for the Guardian. You were in Greece, so I spoke to ex-members and Ben Pritchard.

MES: Oh was that you? It was good, that one.

TC: Yeah. Was it alright?

MES: It was great, that one. That’s pretty funny, because on that sing Portugal that I was telling you about, I actually cut that out and said read a bit of that out, and they only read about three lines of it. So you can sue as well. How did you get in contact with them?

TC: Through band websites, and stuff.

MES: I’d like to keep that actually. I think they threw it away out of jealousy because there was a lot of ex-members in it. It disappeared very quickly.

TC: I guess your band are in their mid 20s, so it’s like two generations down. And in music terms, it must be about five generations.

ELENA: I must say they seem very old fashioned. They listen to things we never listened to. They listen to what their parents listened to.

TC: In love with their mum and dad’s Neil Young collection. My dad listened to Wagner. He despised rock n roll.

MES: Yeah [laughter] My dad listened to military groups. Black Watch and stuff like that.

TC: There’s that real leakage between generations. It must affect the music somehow.

MES: Do you not see it?

TC: Do you think there’s a future? Do you want to carry on with it?

MES: I’m alright for the time being. It’s more than necessary to do it. Just wait till tomorrow’s Eurovision. That’s what we’re waiting for, isn’t it Elena? You’ll see the future tomorrow. By Saturday night.

TC: What’s your opinion of what’s written about you?

MES: The thing about browsing through these books, you don’t find out anything about me at all, do you?

TC: Do you think there’s a bit of a myth about you, a mythological Mark Smith?

MES: Too much, yeah. If you go round the corner from here there’s like a mosaic of me on the corner. But nobody knows who it is, because it’s got like all these people from Coronation Street. I’ve walked past it loads of times and never noticed I was in it. Like, who’s that, you know what I mean? I thought it was like Jarvis Cocker behind some Coronation Street actor’s face.

ELENA: I just came past there. They’ve put a new one up as well.

TC: Is there much going on in the Manchester scene?

MES: I don’t know, I haven’t been home for three months, Tim.

TC: Do you still like to go and check things out?

MES: The Seeds were on, the American garage band, they were on on Oxford Road, but I didn’t get to get there because I broke my fucking hip. Finding out is impossible.

TC: Do you like the Elvis style cover for the Best Of?

MES: What can you say, y’know?

TC: If you flick through the tracks, do any stand out, or sum up a particular period?

MES: Whoever did it did a good job. The great thing is they’ve got the track from the new LP. It’s all very good. Cropdust is the one that forecast the Twin Towers. Powder Keg forecast the Irish bomb and all that. I think it’s alright actually. Whoever did it was smart. I’d listen to this one. That’s the one I’d recommend. I wouldn’t recommend any of the others.

Dear reader, if you made it to the end, congratulations.

Now go.

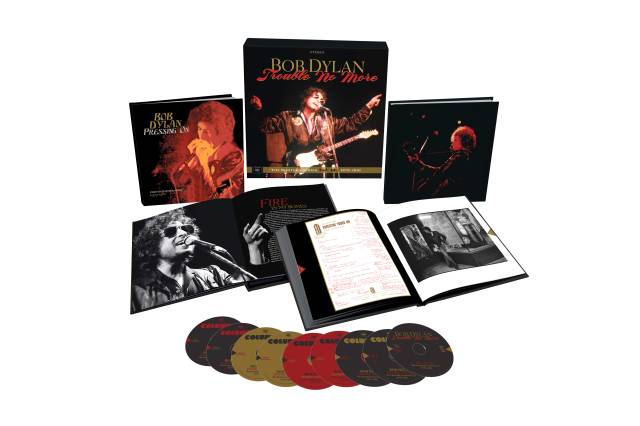

The Toronto recordings [which feature on the deluxe set and on the Trouble In Mind film] were spread over several days, with three cameras. It was a big thing that we were going to do this, and then no one heard anything more about it. They sat on a shelf for years, and now they’ve put it out. They have really done a good job editing it, and it’s just fantastic, the sound and the close-ups are really good.

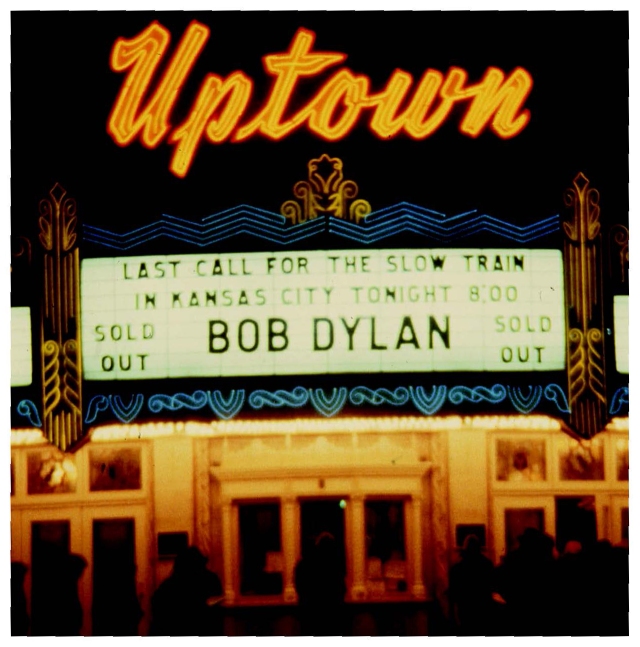

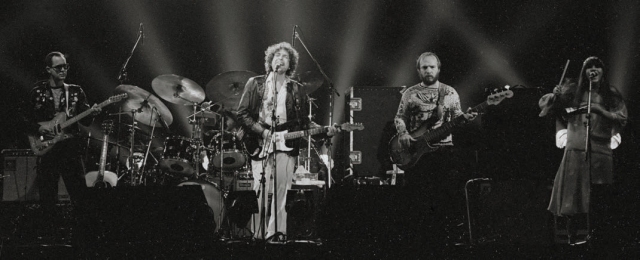

The Toronto recordings [which feature on the deluxe set and on the Trouble In Mind film] were spread over several days, with three cameras. It was a big thing that we were going to do this, and then no one heard anything more about it. They sat on a shelf for years, and now they’ve put it out. They have really done a good job editing it, and it’s just fantastic, the sound and the close-ups are really good. from Jerry Garcia to Maria Muldaur and Mike Bloomfield, all these people came and sat in with us. It was exciting being in the same spot for a couple of weeks. But the newspapers – one review was headlined, God-Awful Dylan. Most of the press was so bad, Bob told me once he called up one of the reviewers, got his number, and called him on the phone, and when his wife answered and he could hear the sound of children in the background, he was so shocked that this dude would have a wife and family that he was speechless and hung up. [laughter] Like, what in the world are you writing about me, man, and then thinking, my God this guy’s got a wife and kids… I don’t even know what to say.

from Jerry Garcia to Maria Muldaur and Mike Bloomfield, all these people came and sat in with us. It was exciting being in the same spot for a couple of weeks. But the newspapers – one review was headlined, God-Awful Dylan. Most of the press was so bad, Bob told me once he called up one of the reviewers, got his number, and called him on the phone, and when his wife answered and he could hear the sound of children in the background, he was so shocked that this dude would have a wife and family that he was speechless and hung up. [laughter] Like, what in the world are you writing about me, man, and then thinking, my God this guy’s got a wife and kids… I don’t even know what to say. We’d rehearse all those songs in Bob’s studio, and Every Grain of Sand was really informal. Everyone had taken a break and gone off, to do whatever they were doing, and Bob and I and Jennifer Warnes were standing around the studio, and Bob started playing guitar. I started playing along with him, and they sang. It was very informal, and it came out really great. Caribbean Wind was a funny incident, I don’t know what versions they have on the boxed set but we got a call from Jimmy Iovine, one of these guys who thought, if I could just get Bob in the studio with the A-team guys, and really do a good basic track, all that stuff. ‘It’ll be huge, it’ll be great’. So he got all of us down early to Studio 55, an old studio that they had redone. An A-team LA pop music studio of 1981. He put me and Dave Mansfield in a room at the back. I had mandolin, Dave was on fiddle, and they had Jim boxed in with baffles and all this stuff, everything separated, everything discrete, and eventually Bob shows up with his guy, whoever was helping him out at the time, running errands and things, and he’s standing there, and they start telling him, Hey Bob this studio is where they cut White Christmas, because Bob loves old studios and is always looking for old studios and mics and stuff, and then they play this track of Caribbean Wind that they want Bob to sing over, and he stands there and listens to it straight-faced, waits until it finishes, and turns to his guy and he says, go get me the music for White Christmas because I can’t cut any of my music in here. [laughter]

We’d rehearse all those songs in Bob’s studio, and Every Grain of Sand was really informal. Everyone had taken a break and gone off, to do whatever they were doing, and Bob and I and Jennifer Warnes were standing around the studio, and Bob started playing guitar. I started playing along with him, and they sang. It was very informal, and it came out really great. Caribbean Wind was a funny incident, I don’t know what versions they have on the boxed set but we got a call from Jimmy Iovine, one of these guys who thought, if I could just get Bob in the studio with the A-team guys, and really do a good basic track, all that stuff. ‘It’ll be huge, it’ll be great’. So he got all of us down early to Studio 55, an old studio that they had redone. An A-team LA pop music studio of 1981. He put me and Dave Mansfield in a room at the back. I had mandolin, Dave was on fiddle, and they had Jim boxed in with baffles and all this stuff, everything separated, everything discrete, and eventually Bob shows up with his guy, whoever was helping him out at the time, running errands and things, and he’s standing there, and they start telling him, Hey Bob this studio is where they cut White Christmas, because Bob loves old studios and is always looking for old studios and mics and stuff, and then they play this track of Caribbean Wind that they want Bob to sing over, and he stands there and listens to it straight-faced, waits until it finishes, and turns to his guy and he says, go get me the music for White Christmas because I can’t cut any of my music in here. [laughter] I really love Pressing On, from Saved. That is very funky, one of the funkiest things we ever did. I like that one a lot. Every Grain of Sand is another of my favourites, because it came down so naturally, but then all of them came down pretty naturally. I think we’d played most of the other songs a lot on the road, so they were a little more worked out. That’s always the thing Bob tried to avoid. He wanted to stop people getting a part that they’ll play every night, which tends to happen. You find something that works and you stick with it and the next thing you know you have this set- in-stone arrangement. Pressing On was more spontaneous, because I don’t remember us playing it as much as we did the other songs, like Saved. Now Saved is pretty great, especially when you hear these new live mixes. And Solid Rock, that’s a really good one.

I really love Pressing On, from Saved. That is very funky, one of the funkiest things we ever did. I like that one a lot. Every Grain of Sand is another of my favourites, because it came down so naturally, but then all of them came down pretty naturally. I think we’d played most of the other songs a lot on the road, so they were a little more worked out. That’s always the thing Bob tried to avoid. He wanted to stop people getting a part that they’ll play every night, which tends to happen. You find something that works and you stick with it and the next thing you know you have this set- in-stone arrangement. Pressing On was more spontaneous, because I don’t remember us playing it as much as we did the other songs, like Saved. Now Saved is pretty great, especially when you hear these new live mixes. And Solid Rock, that’s a really good one.