In the land of the Hairy Hand

Some paintings and their attendant field drawings, derived from the St George’s Day weekend, and at the bottom, two from New Year’s Day 2015-2016, in the fine company of moor walker extraordinaire Mr Will McCarthy. followed by the original text of a feature run by Dartmoor Magazine last year, about life on Powdermills Farm in the 1970s.

But to begin, a poem I first read at a folk night run by Bill Murray at The Devonshire Pub in Sticklepath, with Jackie Oates and The Claque among the players. This drew applause for its brevity. People don’t expect that from poets.

Red Flags

Fine rains and wild grasses

spill between rocks

by the sheep shearing pens.

Red flags are up on the range,

the farmer’s son driving cattle

to the fields below the moor,

the spring stars set in their cavities,

the haze in the late air

of wing hover and planetary

influence, the delicacy

of the moon’s position.

-

-

Watern Tor, 2017

-

-

Watern Tor, 2017

-

-

Towards Widecombe in the Moore from Top Tor, 2017

-

-

Towards Widecombe in the Moor from Top Tor, 2017

-

-

Wild Tor with apple blossom, 2017

-

-

Wild Tor, 2017

-

-

Will’s garden, Chagford

-

-

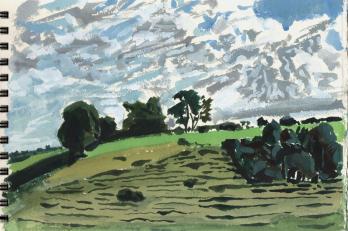

Trees behind Will’s garden, Chagford

-

-

From Fur Tor

-

-

Fur Tor, 2015-2016

The Blue Cottage

What I knew of the moor was a matter of family history. Mum and dad had been visitors since the late fifties, and Dad’s ancestors were Dartmoor men, builders and farmers with parish records going back to the 1720s. Some of them old men with young wives, labourers from the villages of Ilsington and Liverton, where there’s a Cumming Crossroads. Could we see something of ourselves there?

Long summers and fragile Easters largely made up the family’s moorland calendar. Dad painted and drew the moor we knew and lived on, and the vast landscapes beyond, sweeping slopes scored with ancient mine workings, fearsome muses, stone circles, standing stones, kists and dolmens as well as the naturally, spectacularly weathered granites atop the famous tors – the ragged profile of Old Crockern and his ilk. Through the Fifties and the Sixties – the rock n roll years – the growing family would bivouac on a patch of emerald green grass beside a russet brook, the Cherry Brook, on a farm called Powdermills in the middle of the moor, north of the B-road between Mortonhampstead and Princeton, with its prison.

Powdermills had been chosen in the 1840s as a site suitably remote enough for the making of gunpowder, the ripe charge of saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal. The land was littered with ruined granite outhouses, workers’ cottages, two giant chimneys, and leats, channels and clitter-filled drops that once housed water wheels powered by the Cherry Brook to filter out impurities from the finished product. The gunpowder was delivered to local magazines by horse or steam and from there to the quarries and mines that blew their way into the earth for metal and stone. Some of the tin workings in these parts are very ancient indeed. Without them, there wouldn’t have been any Bronze Age.

The farmhouse had been the foreman’s house, the farm buildings workers’ cottages. There is a story of one worker, by the name of Silus Sleep, who chose to eat all his day’s meals in the morning – so that in the event of an explosion, he would meet his maker on a full stomach to soften the blow. Two testing mortar were set either side of the track from the road. Three thousands US troops were station at Powdermills in the months before D-Day and a group of them took the cannon with them. They were retrieved at Plymouth Hoe and returned to the moor, and to Powdermills, where we’d clamber over them to play.

Storms lash Dartmoor even in the height of summer, and there were floods, collapses and other camping calamities until dad gave up bivouacking for one of the farm cottages, The Blue Cottage, hired from the Duchy for seventy pounds a year, and one of a row of two between milking parlour and barn that looked towards Bellever forest – post war pine and Forestry Commission pathways. It rose up dark and solid towards the summit of Bellever, like a troubling dream, the approach to the peak ringed by wild blueberry bushes yielding handfuls of tiny bittersweet fruit to assiduous foragers and thirsty mouths. I remember following a stream through the forest, as if it were a fairy story, taking you deeper into the wood but forever holding the light of the sky below the crowns of the tall dark handsome pines.

The Blue Cottage had a tiny front garden, and a paddock ran the full length of farm buildings behind us. In shearing and lambing season, the farmer George Stevens would round up flocks from the moor – whistling and calling his dogs up the slow slopes of Longaford and Higher White. Sleeping through the sound of several hundred sheep in the paddock at night, as if the sound itself took on the properties of wool and pillowy warmth, a quiet kid like me would feel the whole of the universe expressing its sheepness.

We drew water from a well using a long iron hand pump, and lit the rooms with oil lamps and candles and the light of a rayburn. In later years, the landowner Mr Russell had a generator installed, but our cottage was not connected to the 20th century in any direct manner, and I relished the time travel. It was haunted, too. The voice in the ear in our parent’s bedroom. All drowned out by the generator sat shaking and growling in the old barn where dad and Mr Stephens once tended a dying bull ‘whose blood had turned to water’, like the Mass in reverse, and a bull, too, the creature of the cave wall, something as old as the oldest human workings of the moor.

Red Flags is from The Rapture, published in 2012 by Salt, and available, still, from their website