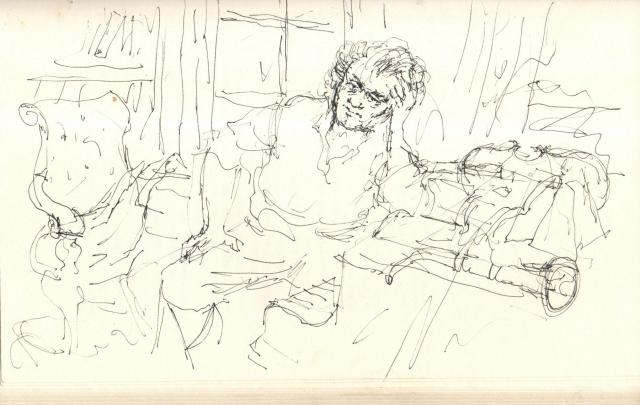

(above, Beethoven in his rooms in Vienna, by Peter Cumming, circa 1993)

Published here and by the Boston Musical Intelligencer, what you are about to read casts Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony into a fresh light, stripped of historical excesses, and drawn from the conductor Benjamin Zander and the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra’s outstanding performance of what is arguably the greatest piece of music ever written, at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s Southbank on Saturday 18 March 2017.

Beethoven, Revolution and Number Nine approaches the Ninth from the raw, the vernacular, the immediate, in view of the classical but focusing on the vitality of the experience of being in the concert hall with this music as it is being made, and drawing on a generously expansive and informative conversation with Zander in its aftermath. His and the Philharmonia’s new recording of the Ninth will appear later this year.

Benjamin Zander is conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, a post he has held for 39 years, and his radical account of the Ninth is the first to incorporate all of Beethoven’s instructions concerning tempi, and proved to be a revelation to many who were there, and revolutionary, too, in how it still speaks to us now, in the present tense, not as a remote monolith but very much alive and very close.

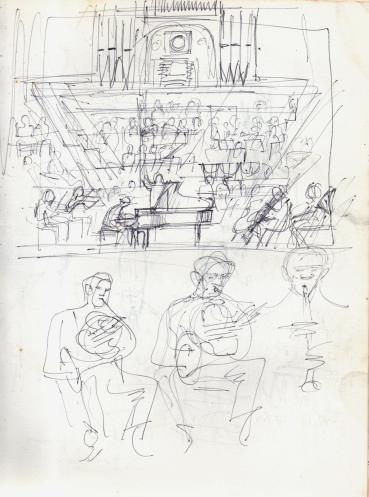

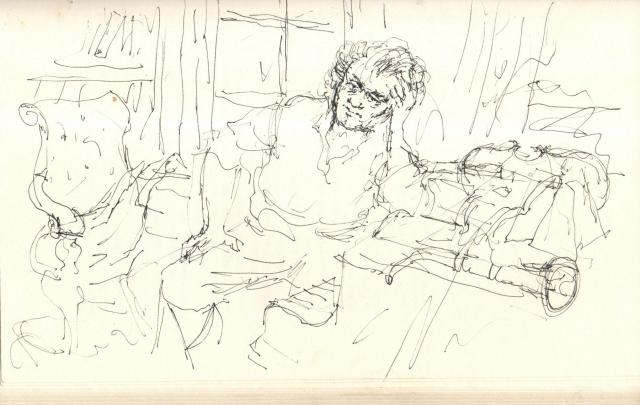

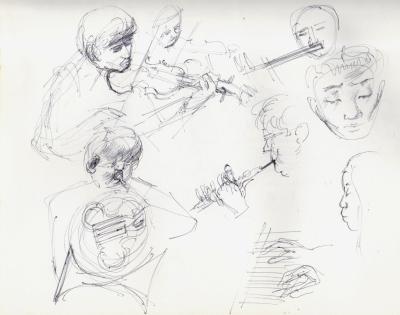

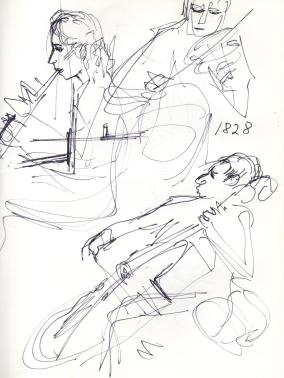

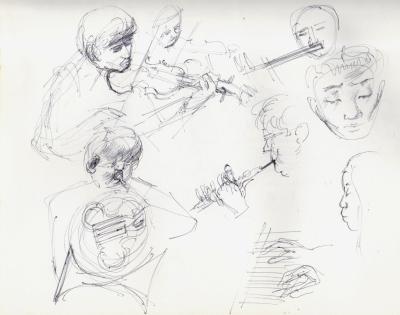

The drawings that illustrate the text are by my father, the artist Peter Cumming, and taken from a number of the sketchbooks he kept throughout his life. The above drawing was made in the frontispiece of Michael Hamburger’s Beethoven’s Letters, Journals, Conversations.

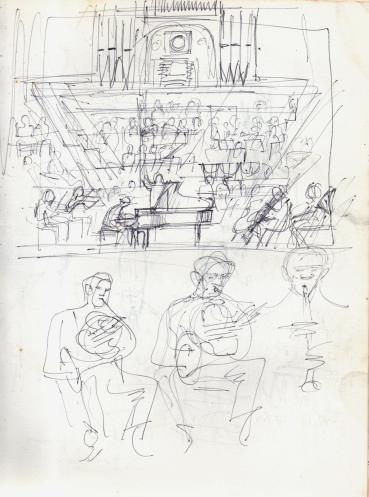

The Orchestra, Peter Cumming, circa 1960s

Please take your seats. The performance is about to begin.

The Royal Festival Hall, Southbank, 18 March, 2017. 730pm

Revolutions – they tend to date quickly and age very badly. But sometimes the music they inspire remains immortal. Such is the case with La Marseillaise, and so it is, too, with Beethoven’s Ninth, one of the most recognisable and globally loved of all pieces of music, and whose roots, in the poet Schiller’s revolutionary-era Ode To Joy, date back to the turbulent 1790s. And while the Choral Symphony is just a few years short of its 200 birthday, and familiar enough to anyone with a sprinkling of musical knowledge, if conductor Benjamin Zander is right, we haven’t been listening to the symphony as Beethoven wrote it at all.

Zander is conductor of the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra, and has spen t a lifetime studying the Ninth, and in March he came to London and the South Bank to lead the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra through a radical restoration of Beethoven’s original tempi, which have been largely ignored or dismissed as unplayable, and the errors of a deaf and disturbed old man since Wagner made a colossus out of the Ninth with his Bayreuth premiere of 1872. Zander’s energising 58-minute account shaves about a quarter of an hour from the standard performance, and his recording with the Philharmonia will be released this Autumn, and promises to change the way we respond to what is arguably the greatest piece of music ever written.

t a lifetime studying the Ninth, and in March he came to London and the South Bank to lead the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra through a radical restoration of Beethoven’s original tempi, which have been largely ignored or dismissed as unplayable, and the errors of a deaf and disturbed old man since Wagner made a colossus out of the Ninth with his Bayreuth premiere of 1872. Zander’s energising 58-minute account shaves about a quarter of an hour from the standard performance, and his recording with the Philharmonia will be released this Autumn, and promises to change the way we respond to what is arguably the greatest piece of music ever written.

The conductor’s preoccupation with Beethoven’s original tempi goes back to the 1980s, and a project with the BBC to record a Ninth at the radically faster times indicated by the composer in his annotated scores. The project stalled when the broadcaster asked Zander to use period instruments; the conductor preferred a modern orchestra. His extensive notes and research into the world of Beethoven’s metronomic markings would later be passed to Roger Norrington for his 1987 recording, while Zander released his own account with the Boston Philharmonic Orchestra five years later in 1992, with John Eliot Gardner’s excellent Philips release following in 1996. “At the time, I felt very annoyed,” says Zander of Norrington’s recording, “but subsequently I was delighted because I needed another 35 years of work.” He laughs. “At the Royal Festival Hall I got a chance put forward many different things that I didn’t know about in 1980.”

Zander’s reading of the Ninth is a vigorous raising of the symphony’s original fiery spirit, rather than its monolithic reputation

Commissioned in 1822 by the Royal Philharmonic Society for just £50 (and initially dismissed and disdained by London ’s august critics’ circle), the Ninth was revolutionary then, and remains so today. Its colours never fade – it is only our perceptions of it that change, and Zander’s reading of the Ninth is a vigorous raising of the symphony’s original fiery spirit, rather than its monolithic reputation.

For us listeners, the Ninth is a deeply internal voyage, with very powerful communal effects. It gets to you; it’s in that spectrum that penetrates like an X-ray. It is music with the quality of urgent speech but from a place that is generally beyond words, if close to the inner voice, and the inner ear; it’s music that speaks inside us, and its immediacy extends from the contexts of its creation to the reception we give it today.

“It was a very troubled time then, as it is for us now,” says Zander, talking a few days after his triumphant Ninth at the South Bank, that saw the audience rise for an unprecedented 15-minute ovation. “And the message of the Ninth is more relevant than ever. It is not a description of what is, but a presentation of what could be. It is music for our time.”

By setting Schiller’s revolutionary-era ode, Beethoven was harking back to the spirit of the revolutionary 1790s, of intellectual, cultural and political release as the European Enlightenment exploded into anti-monarchist revolution, which itself exploded into self-consuming violence, Napoleon, empire, continent-wide warfare, Waterloo and, by 1814, the Congress of Vienna, with Europe’s royal houses recalibrating power back to something they could understand – complete top-to-bottom control.

The message of the Ninth is more relevant than ever. It is not a description of what is, but a presentation of what could be. It is music for our time

Which means that, by the 1820s, the liberation fervour of the 1790s was long gone, as far away from the middle-aged Beethoven as the optimism and fervour of the 1960s is from us. The composer’s troubled times, and ours, are coupled, if not at the hip, then at the ankle. The Ninth was created in hostile conditions, under the dystopian eyes and ears of Metternich’s secret police – they had a fat file on Beethoven, and they added to it. Like the Stasi of the 20th century, they were listening.

And we still listen. This angry, anguished and disabled man’s late testament to personal despair, resolution, acceptance and ultimate sense of shared liberation from within remains the European Union’s anthem, even as the EU project teeters and buckles under the weight of banking algorithms, Brexit, populism, and debt. The Ninth still speaks to us, and in the present tense. And how it speaks.

The first movement, that cosmic egg breaking open among the strings, is a sound structure suspended in the first ripple of space-time

Under Zander’s baton, it’s as if two centuries of varnish, candlewax, and post-Romantic indulgence and mythology has been cleared from the surface to illuminate the depths. The smoky accretions of the 19th-century masters and their 20th century successors have been simmered off by the process of patient reduction and a return to the source.

The first movement, that cosmic egg breaking open among the strings, is a sound structure suspended in the first ripple of space-time. And then the opening descending riff, the armature around which the movement unfolds, expands, retreats and reiterates. In the grand recordings of Toscanini or Furtwangler there is something gigantic and ponderous in this first movement, a great creature of great depths. With Zander and the Philharmonia the depths remain, but our attention deepens, and what we hear is more translucent, fresh, immediate, and the underlying dynamic in Zander’s account here and in the whole symphony, is of compression and release – great compression, with the potential to blow the roof off – and great release, of exultation, of orgasm, of liberation and of union.

The muscular riffs and fanfares of the second movement speed along at Beethoven’s indicated tempo, with the trio section cramming in four notes to the bar instead of three, at a speed deemed impossible, until now. It is not only possible, but realised by Zander and his players in a way that no other performance has achieved, the extraordinary detail of the composition brought out with a rare clarity and sense of space. It’s the Ninth stripped of grandeur and High Romanticism’s self-regard.

The muscular riffs and fanfares of the second movement speed along at Beethoven’s indicated tempo, with the trio section cramming in four notes to the bar instead of three, at a speed deemed impossible, until now. It is not only possible, but realised by Zander and his players in a way that no other performance has achieved, the extraordinary detail of the composition brought out with a rare clarity and sense of space. It’s the Ninth stripped of grandeur and High Romanticism’s self-regard.

The extraordinarily beautiful third movement unfolds its secrets one by one, lotus petals opening in a soft southerly breeze of wind and strings, and though taken at a faster pace, losing none of that sense of timeless suspension, of infinite space and utter calm descending into musical form.

The extraordinarily beautiful third movement unfolds its secrets one by one, lotus petals opening in a soft southerly breeze of wind and strings

At its close, Zander barely pauses before launching in to the ‘Horror Fanfare’ that hurls the final choral movement into being. Again, the feeling is of hearing something anew, afresh, in real time, in our time, cleared of the dirt and grease of accumulated performance traditions. For this is an Ode to Joy that’s bare, forked, and naked. There’s a renewed sense of excitement as it rounds up and corrals signature themes from throughout the symphony to create a sense of time inverted, dispersed, eddying in the flow of music before revealing its signature tune – Beethoven drafted it painstakingly to get it right, in the little sketchbooks he carried with him everywhere, his blank-paged familiars. The chorus is a revelation, more nuanced and dynamic, no longer turned up to 11 throughout. Deep within, the Turkish March is simple, humble, haunting, as around it the choir and orchestra rises and falls in peaks and valleys, turning and weaving as the dynamism of that folkish little tune unfolds itself, over and over, like the secret of perpetual motion in sound.

At the Royal Festival Hall, before Zander and the Philharmonia, as the drama of the music – and our reception of it – unfolds, it is hard not to feel awe before the Ninth, to hear in the flesh rather than in a recording the music that lies in all those little sketchbooks, all the sheet music, the unsettled scores, all the mess and anguish and temper, the shabby rented rooms of the grey-haired, shock-haired, deaf-as-a-post composer, on his own here, quite alone, the giant who, at the Ninth’s premiere, needed to be tapped on the arm and turned to face his audience by a pretty young soprano, a woman whose mouth the composer had just filled with the most beautiful music. It takes your breath away.

It was quite extraordinary; people said they hadn’t seen a reaction like it before – but it is Beethoven who got the reaction

As Zander brings it on home in the last few bars, after the last note there is the briefest silence before the first wave of applause builds across the Royal Festival Hall, a standing ovation that seems to go on and on. “It was quite extraordinary; people said they hadn’t seen a reaction like it before,” says Zander afterwards, adding: “It is Beethoven who got the reaction; I was the servant who enabled that to happen with the orchestra and the choir and the soloists.”

And now it is the orchestra, the choir and the soloists who stand with Zander, as the audience around them stands, as audiences have done over the past two centuries, right back to that seat-of-the-pants Viennese premiere of 1824, with Beethoven being turned to the audience, all of us getting to our feet and bringing our hands together in the spirit of the Ninth.

A 19th-century depiction of Beethoven at the Ninth’s premiere

“The most touching and moving thing,” says Zander, “was that this man, who was deaf, who had no connection, no woman in his life, no companion, cut off from the world in terrible conflict with his nephew, with the authorities, and having to move house constantly, one of the saddest individuals and ill to boot, wrote a piece which brings the world together. That is the most extraordinary idea, the most moving idea, and there it happened in concert on that Saturday night.”

Europe today is in shabby shape, like Beethoven’s rented rooms, piss-pot under the piano, the keys out of tune, debts everywhere, shouting in the street, fears that the treaties binding us together will not last the way that Beethoven and his Ninth will last, that little tune of liberation and joy singing away in its handful of notes. But whatever our troubles, the music lets us in, brings all of us here to this place with one purpose, to realise the greatest of symphonies, to unleash the Ninth and to experience for ourselves, for a moment, its spirit of joy.

Tim Cumming

The composer in his rooms, by Peter Cumming, circa 1960s (JS Bach?)

You may now turn on your mobile phones and tweet madly about this piece.

FINALE: Watch Benjamin Zander at TED

t a lifetime studying the Ninth, and in March he came to London and the South Bank to lead the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra through a radical restoration of Beethoven’s original tempi, which have been largely ignored or dismissed as unplayable, and the errors of a deaf and disturbed old man since Wagner made a colossus out of the Ninth with his Bayreuth premiere of 1872. Zander’s energising 58-minute account shaves about a quarter of an hour from the standard performance, and his recording with the Philharmonia will be released this Autumn, and promises to change the way we respond to what is arguably the greatest piece of music ever written.

t a lifetime studying the Ninth, and in March he came to London and the South Bank to lead the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra through a radical restoration of Beethoven’s original tempi, which have been largely ignored or dismissed as unplayable, and the errors of a deaf and disturbed old man since Wagner made a colossus out of the Ninth with his Bayreuth premiere of 1872. Zander’s energising 58-minute account shaves about a quarter of an hour from the standard performance, and his recording with the Philharmonia will be released this Autumn, and promises to change the way we respond to what is arguably the greatest piece of music ever written.

The muscular riffs and fanfares of the second movement speed along at Beethoven’s indicated tempo, with the trio section cramming in four notes to the bar instead of three, at a speed deemed impossible, until now. It is not only possible, but realised by Zander and his players in a way that no other performance has achieved, the extraordinary detail of the composition brought out with a rare clarity and sense of space. It’s the Ninth stripped of grandeur and High Romanticism’s self-regard.

The muscular riffs and fanfares of the second movement speed along at Beethoven’s indicated tempo, with the trio section cramming in four notes to the bar instead of three, at a speed deemed impossible, until now. It is not only possible, but realised by Zander and his players in a way that no other performance has achieved, the extraordinary detail of the composition brought out with a rare clarity and sense of space. It’s the Ninth stripped of grandeur and High Romanticism’s self-regard.